When the writing gets tough, the tough turn to poetry

How the fears of John Keats speak to me as writer's block strikes

I have, very recently, been writing notes on Substack bemoaning my lack of progress with my writing. I appreciate it gets rather boring when writers say they can’t write, as if we are all sitting there with hand to forehead, surrounded by balls of screwed up paper waiting for the muse to strike. Writing is seen by many as hardly a job at all, and to be honest the amount we put on our tax returns each year does suggest it can’t be one for much longer. But as much as people rely on writers for so much more than they realise, we generally don’t get much sympathy, except from our writer friends who in the main are similarly suffering (suffering similarly?)

Anyone who knows me understands how quickly I reach out to poetry at times when I think my writing days are over. Even if things have gone relatively well, there is always that creeping doubt that besets the imagination, especially of those like me, prone to anxiety. It can undermine almost everything you have worked to achieve. Poets can distil into few words what I find difficult to express in paragraphs.

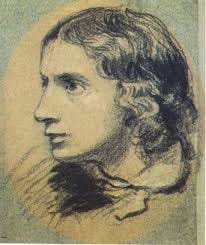

I've discussed the Romantic poet, John Keats, on here before. I actually wrote a whole book about him. I have been reading him from around the age of 12, and he appears, alongside Robert Frost, Wilfred Owen, and various later 20th and early 21st century poets, among my most frequently read. Poets can speak to you of joy, of life surpassing hope, of love (I am shortly to read the moving words of ‘I carry your heart with me…’ by e.e. cummings at my daughter’s wedding) and of failure and loss

So let’s turn to John Keats…

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain,

Before high piled books, in charact’ry,

Hold like rich garners the full-ripen’d grain;

When I behold, upon the night’s starr’d face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour,

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love!—then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till Love and Fame to Nothingness do sink.

In 1818, when Keats wrote this, he was just beginning to mature as a poet, leaving behind early friendships that limited his work or took it in directions that ill-suited him. By the autumn of that year he would be starting the fourteen or so months of startling creativity that produced much of the work for which he is best known today – the ‘Great Odes’, The Eve of St Agnes, La Belle Dame Sans Merci, Lamia – his poetic development happened with astonishing speed. In the earlier months of 1818 though (this sonnet was sent in a letter to his friend John Hamilton Reynolds in the January) he was still finding his original ‘voice’ and working through his poetic philosophy.

Full of this demon self-doubt, fearing failure, recognising that even given his talent he would have to work hard to achieve ‘greatness’ he seems almost desperate and full of anxiety in the sonnet: will I be given enough time to achieve success, to say everything I want to say? Will I find that ‘real’ love?

I have always thought this poem has other complex meanings. It speaks to me as a writer in a way few poems can, by expressing the fear and doubt that besets many of us, whilst using language that hints at success and completion – the ripening of the grain and the ‘fullness’ suggesting a successful harvest of a fertile imagination. It inspires with the image of the nourishing nature of art itself as books are filled with words as the ‘garners’ (the granaries) are filled with grain. But our futures are cloudy, and shadowed. All writers (should) doubt themselves at times. Whatever his concern for the future, however, Keats has an essential belief in the possibility of his genius. Love and fame need not be the essential features of his life. Keats is a philosopher as well as a poet (his letters are wonderful streams of spontaneous and deep thinking) and the importance thought, of a working through of the myriad anxious thoughts that beset us, is as valuable as setting them down on paper.

Of course you can just read this as a beautiful, if melancholy, poem that presages rather spookily Keats’ early death. It is the first poem I learned off by heart, aged just twelve, and it has stayed with me ever since; its regular metre suiting the rhythm of my stride as I recite it to myself, walking quickly to keep up with our dog on a long walk.

Not everyone wants to be a writer, but we all have doubts about the future, especially at the moment. The challenges of Artificial Intelligence, the determination of world leaders to become cruel, greedy and violent, climate change. Yes, you can read the poem as one of potential disappointment, fear of failure and anxiety at a lack of success. But the last lines seem to me to look out over the edge of our world, casting old thoughts aside and offering us a chance to put things into perspective.

I know that I will write again in the future, and people on Substack have been kind, suggesting I cease to give myself a hard time and wait until my daughter’s wedding is safely over. A fabulous venue, a beautiful couple. But beautiful things can be stressful too!

We write from what we know, and I don’t want to write about stress. I must assume at this juncture, when words won’t come, and I feel generally a bit ancient and past it, that I must simply wait and hope. After all, the wedding is only 6 weeks away.

So, I will read this poem often over the coming weeks to remind myself that with luck and hard work I can achieve good things. If not, I’ll go into wedding planning. Not.

Thank you for reminding me of Keats. I'll look up your book about him.

You may have an idea in a book/feature on writers' block? Or weddings worked quite well for Jane Austen? I lived in a writers' block once in Westbourne Park, it was full of asbestos and eventually pulled down...